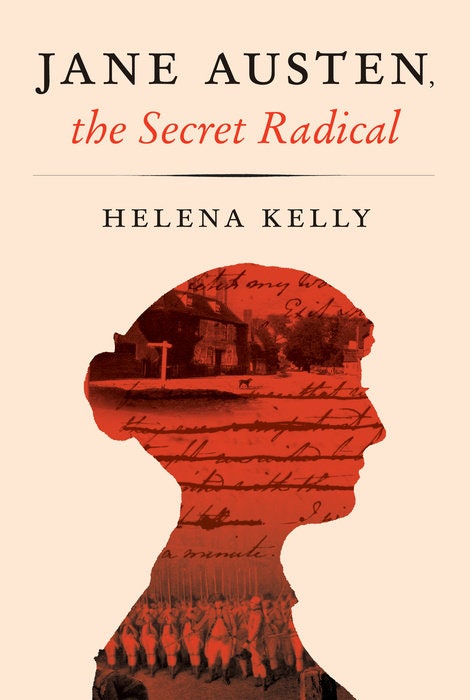

Kelly is far from the first critic to engage with political issues in Austen’s fiction. At one point, she describes Elizabeth Bennett in Pride and Prejudice as “a radical” because she “knows her own mind” and “reserves the right to decide questions for herself.” Does accepting the idea that Austen was a secret radical, who wrote, according to one reviewer, “about the burning political issues of the time,” make reading the novels any more pleasurable or interesting? Or is it necessary for us to redefine Austen as politically engaged and indignant in order to respect her as a serious woman writer? Kelly never says, however, what she means by “radical.” Is Austen’s radicalism a political agenda, a feminist critique, a theological question, or just feminine self-assertion? Kelly provides very few clues. To uncover this subversive text, Kelly argues, “we have to read carefully.” Austen couldn’t be “too explicit, too obvious” in her writing, because she lived in a society “that was, essentially, totalitarian.” Instead, Austen planted clues and codes, trusting her readers “to mine her books for meaning, just as readers in Communist states learned how to read what writers had to learn how to write.” In Kelly’s view, Austen’s novels are a kind of samizdat, concealing radical messages beneath their conventional surfaces. The Bank of England will even issue a ten-pound note with Austen’s picture on it.

There will be dozens of exhibitions and commemorations from America to Australia. The bicentennial of her death brings the release of annotated anniversary editions of her novels and critical studies such as The Making of Jane Austen by Devoney Looser and Reading Austen in America by Juliette Wells.

This year is an especially big one for Austen devotees. Most have an expert knowledge of Austen’s six novels, as well as two centuries of scholarship, and their conferences include panels and talks by learned Austen scholars, alongside the balls and excursions. While Janeites love partying and cosplay, they are interested in much more than cream teas. But this time it was the setting for a different kind of eerie displacement: nearly 600 Austen enthusiasts, many wearing Regency costumes, decked out in ribbons and bonnets, and carrying reticules, fans, and parasols. We met in the Fairmont Chateau at Lake Louise in the Canadian Rockies, which was said to be the original of the hotel in Stephen King’s The Shining. Many years ago, I went to a conference of the Jane Austen Society of North America.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)